Isabel Pato: "Civil society can innovate and respond to social and environmental challenges"

The Former coordinator for fundraising at Oxfam Brazil talks to us about the task done by organisations and movements in the country to counter inequalities, local struggles and gives us examples of social innovation and ways to do joint advocacy work.

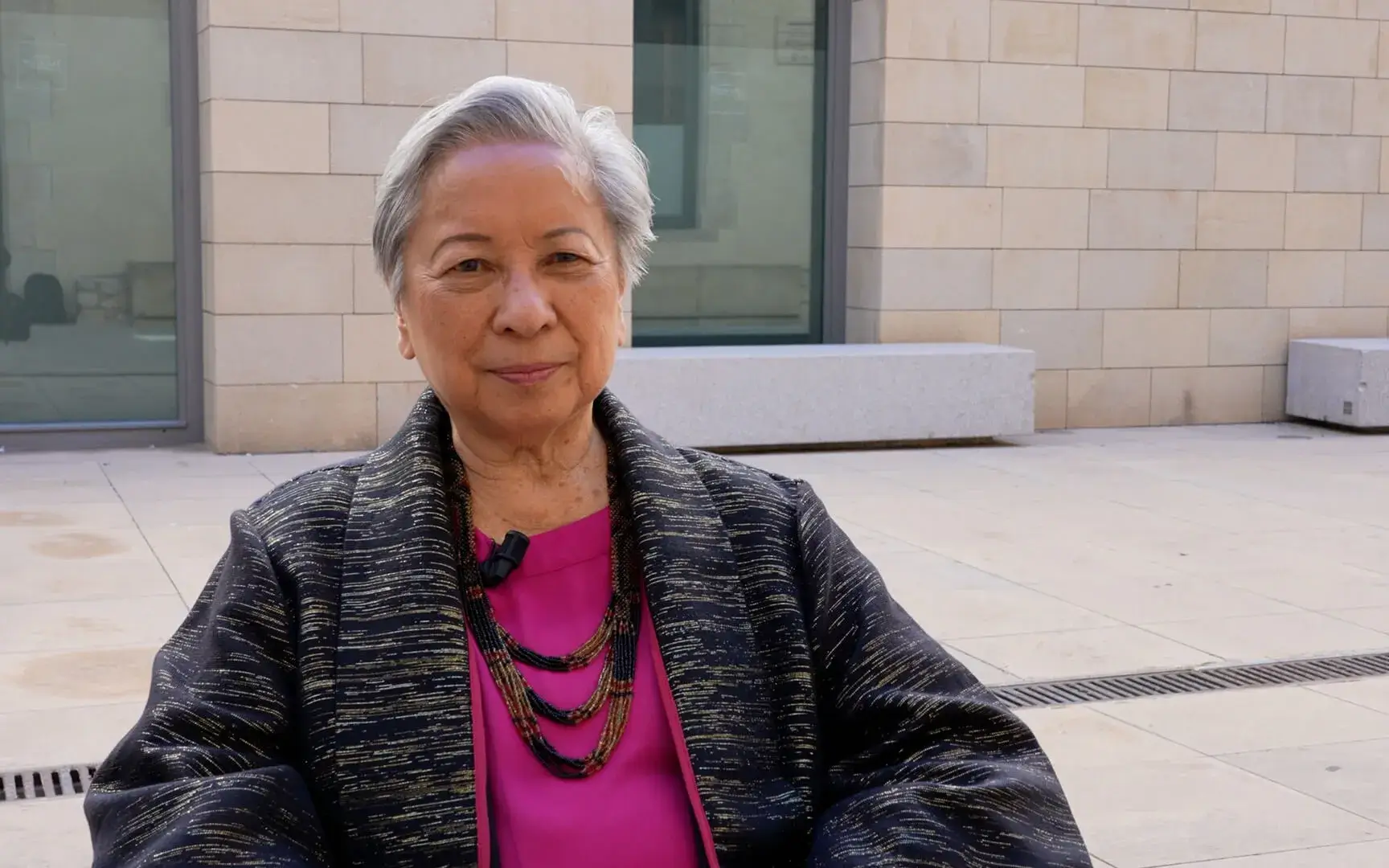

Nonprofit, in collaboration with the Catalan organization Taula del Tercer Sector de Catalunya, has talked with Isabel Pato, an expert in civil society institutional development, fundraising and fostering social innovation. She is also a facilitator for collaborative processes, social innovation and networks.

This interview is one in three that have been conducted to learn more of the social reality in Brazil and the role that non-profit organizations play and must play to have an impact on policies and struggles to fight social inequalities.

Presently she works for Ponte a Ponte consultancy to strengthen Brazilian organisations.

How would you define the social agenda in Brazil? What are the main challenges?

One of the main challenges today is the attack on Brazil’s democracy. There is concern and angst to find out what will happen after Lula’s return to power and to find out how Brazil’s democracy will be re-organised.

Another point of concern is the conjuncture between the environment and society. We must stop the destruction of the Amazon and the habitats of indigenous peoples. We can take it a step further than conservation to learn about these populations. We can pay greater attention to the populations living in these habitats in harmony with the ecosystem to improve the way we relate to the environment.

Luckily, we have seen some measures, such as those taken by Lula electing an indigenous to hold a government ministry for the first time.

There are also global issues that aren’t specific to Brazil such as inequalities, poverty and hunger. Oxfam’s reports are very illustrative in this sense

How are these inequalities felt in Brazil?

In Brazil half of the population lives with some degree of food insecurity: the eat today without knowing if there’ll be food for tomorrow. We can’t only talk of those who go hungry, but also of the fear of not knowing if there’ll be anything to eat in the future.

Inequalities don’t only occur in this field, but also in the way wealth and land are distributed. This polarization of wealth leads to a deterioration of democracy.

Slavery and what we did to indigenous populations is still alive in our collective memory. We cannot wipe this aside. We must call for accountability from those responsible. It is important for organizations to know where we come from and how we’ve contributed to strengthening democracy.

How would you define the Brazilian associative movement?

Brazil’s associative fabric can be broken down to non-profit organisations and foundations.

Now there’s also talk of enterprises with a social impact. It is interesting to think about these organisations in terms of sustainability, since they can sell services and do things…but it’s also important to survive beyond donations and grants.

Then you also have family foundations, institutes for relations with businesses and organizations such as ABONG that have been working to defend human rights and for democracy since the dictatorship.

What is the role of society and especially the younger generations in this social struggle?

Youth organisations are focused on leadership and social organisation, departing from the idea of an organization structures with a board, a chair and a council. Escaping institutionalization. In Brazil they are especially active in large cities such as Sao Paulo, and they foster discussions on new labour relations and new ways of relating to the environment.

Then we have unions. Since their reform and the loss of resources and the change in legislation, union are now very fragile. Nevertheless, their work remains important in rural areas and labour issues protecting temporary workers from growingly precarious jobs.

In this social and environmental area you mention, are there any groups protecting the territory?

Yes, we have the national CoNaq Committee to defend territories and the quilombolas. These are the Afro-Brazilian residents in the quilombo settlements that were created by runaway slaves in Brazil. APIB, the Association of Indigenous Peoples also plays an important role.

Civil society can innovate and respond to social and environmental challenges. This is also true for the peoples of the Amazon, who are better equipped to respond to the complex and inter-related challenge combining social and environmental aspects.

With global challenges such as climate change, we must turn to indigenous peoples and look at how they live and see the planet. They help us to re-think of the way in which we are building our world. These peoples, who are most exposed to overexploitation, possess knowledge that can be very useful to build more sustainable cities.

Does civil society today have enough spaces for participation to have a say in the country’s social agenda?

Historically these spaces have existed and currently with the change in government they Will be strengthened. We need adequate monitoring of public policies and of the government. These organizations supported Lula’s election, and now they must reclaim answers from the government to meet their expectations.

How can the voice of organizations and citizens be strengthened in decision-making spaces?

There are groups living in the periphery of large cities who know how to work to overcome food insecurity through urban gardens. These groups need to be empowered, the community needs strengthening and allowed to participate. It’s important to break away from individualism and recover a sense of the commons and a group identity.

At the onset of the pandemic people had no gas for cooking. Maybe they had food but no gas. Families started sharing their ovens, turning them into community ovens. This is a good example on how important a community is.

Do you have experiences of collaboration with social organisations from other countries? How do you see cooperation among social organisations in Latin America?

There are NGOs present in Brazil that have relations with other territories, like Oxfam, that can help foster South-South relations.

It may be a good moment to recover the World Social Forum as a new meeting point for global civil society. Going back to discuss relations among territories in favour of greater social justice. In Brazil, many local organizations like the ones I mentioned, while fighting for human rights, turned to international human rights’ organisations to denounce the violation of rights in Brazil.

What is your outlook on European agendas? From the social level to European foreign action and the push to strengthen civil society in other countries?

The European Union is one of the most important organizations when it comes to strengthening Brazil’s civil society. It’s calls for support are very important.

The path to joint advocacy is interesting. European and Brazilian organisations should join efforts to do political advocacy with the rest of the world and learn of better funding models and build up resilience.

If you found it interesting, you can consult the rest of the contents of the monograph, as well as the interview with the director of the Polis Institute and the board member of ABONG.

Add new comment