What are the socio-environmental impacts of the clothes we wear? Do we know the path it takes to reach us and where it ends up once we launch it?

These are some of the questions we have asked ourselves and sought to answer. Coinciding with the start of the sales season and just after the Christmas shopping period, SETEM has concluded a participatory process to map the impacts of excessive clothing consumption in Barcelona on the Global South—impacts that could be extrapolated to any part of the world. The map was collaboratively created with the participation of various organizations, experts, and public administrations, all of whom brought diverse perspectives and enriched the discussion. This process was driven by Lafede with the support of the Barcelona City Council.

The clothing sales and consumption model is changing at a rapid pace. Recently, we’ve been talking about ultra-fast fashion, with new brands like Shein entering the market and producing a dress in just one week—from design to packaging—with all the implications this entails. Fast fashion has led to a significant increase in the amount of clothing produced and discarded. Globally, around 100 billion garments are sold every year, and it’s estimated that 73% of them end up in landfills.

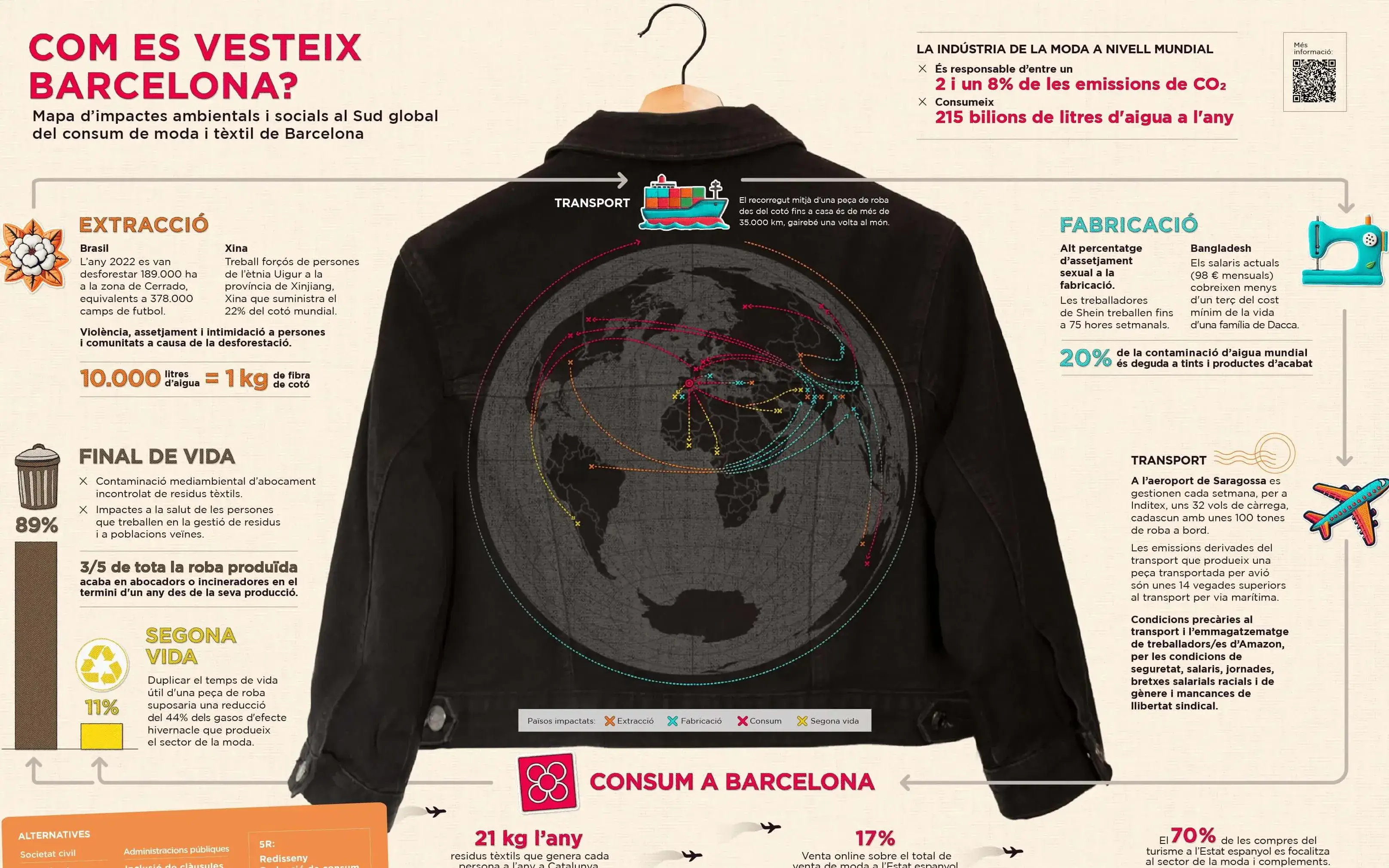

We vaguely recognize that such low prices, which allow us to change our wardrobes so often, must have an impact somewhere on someone, but we are not fully aware of the social and environmental effects involved. These impacts often manifest in third-party countries, as most production occurs outside Europe, in places with weak labor and environmental regulations. To give an idea: the average journey of a garment, from cotton to our homes, spans over 35,000 km—more than a trip around the world. Brands like Zara still transport massive volumes of fast fashion by air, causing significant harm to the climate.

The map simplifies the various stages a garment goes through before reaching our hands. It starts with the extraction of raw materials, a phase that uses vast amounts of water and land to grow cotton and other fibers, leading to deforestation in regions like Brazil. The use of pesticides in raw material production is responsible for approximately 20% of the global contamination of drinking water. Social impacts are equally alarming; forced labor among the Uyghur ethnic group in Xinjiang, China, which supplies 22% of the world’s cotton, has been documented.

The next phase is manufacturing, characterized by highly precarious working conditions, mostly for women. Wages often fail to cover basic living expenses, and overtime is frequently imposed or necessary to make ends meet. Workers face union repression to prevent collective bargaining, gender discrimination, and a lack of health and safety protections.

Once transported and delivered to us, how long do we keep our clothes? In Catalonia, it’s estimated that each person generates about 21 kg of textile waste per year, of which only around 2 kg — less than 11% — is selectively collected. Most post-consumer textiles end up in general waste bins. This is expected to change, and hopefully improve, with the implementation of mandatory selective collection of textile waste across Europe and new measures currently under discussion.

We consider it crucial to promote the extension of a garment’s lifespan starting from the design phase. It is essential that workers in the sector have dignified working conditions and that brands take responsibility for ensuring this. We also share a responsibility: to be aware of the impacts of overconsumption on the planet and people and to think before we buy. Alternatives exist: repair, reuse, and recycle as much as possible.

Additionally, we can make our voices heard and mobilize to demand that brands meet their obligations. To do so, we need to stay informed. Follow the “Robaneta” campaign on social media at @setemcat, where all the latest research is shared, helping us understand the realities faced by affected people and the mobilization actions we organize toward brands and policymakers. SETEM also offers training, exhibitions, and workshops aimed at various audiences through its service catalog. It’s in our hands to learn more and make informed decisions.

Add new comment