Olga Margalef was in Lesvos when scores of refugees were arriving. Anna Sorio visited Petra, after the makeshift camps were being dismantled and the official military camps set up. What has changed?

The Spanish Refugee Aid Commission (CEAR) in its Annual Report published last June, informs on the number of asylum petitions in Europe during 2015: 1,321,600, which is more than double than the previous year and of these, the administrations have resolved favourably just over 300,000. The UNHCR, in turn, warns that the number of forced displacements as a consequence of armed conflicts reached the figure of 60 million people in 2015.

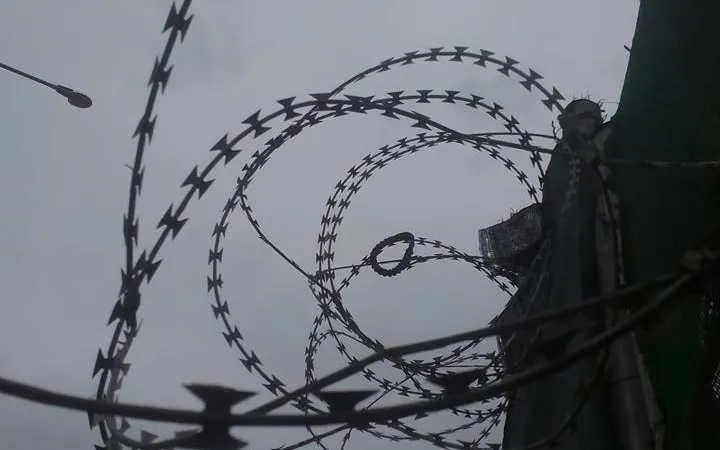

At the European Union, after the message of welcoming launched initially by some heads of state and government, the EU border policy shifted towards hardening the borders and barbed wire fencing, forcing thousands who were fleeing from dramatic contexts to risk their lives. The International Organization for Migrations published in May that over 1,370 people had died in the Mediterranean in 2015 alone. The CEAR stated that the figure actually rose to 3,700 since the mass arrivals started.

Within this context, and according to the report, in 2015 the Spanish State received more than 14,800 asylum petitions, the highest figure ever registered, which however only accounts for 1% of all asylum petitions in the EU. The State took on the commitment to relocate 16,000 refugees. The truth is it only relocated 18.

Olga Margalef is a post doc researcher at CREAF in the UAB. In November 2015 she travelled to Lesvos with three colleagues to help out for two weeks, after which she returned for another week months later. Anna Sorio is a generalist dentist and collaborates with Dentistes Sobre Rodes (DSR), Acció Planetària (Dentists on Wheels, Planetary Action), a nonprofit organisation for solidarity dentistry in Barcelona and in several countries. Last June she joined a team of professionals in the Petra official camp.

Lesvos, November 2015

What reality did you meet when you arrived in Lesvos?

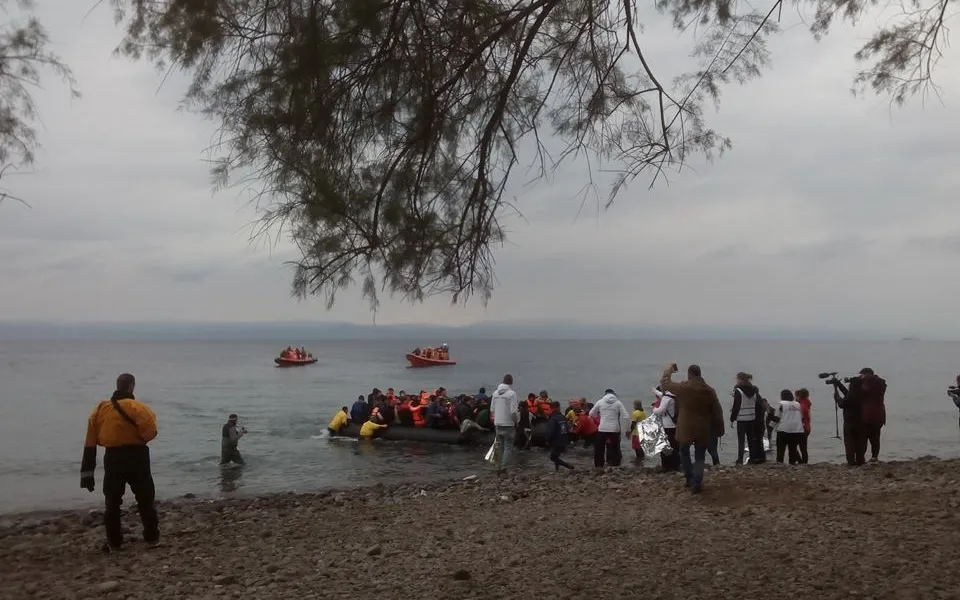

When we arrived, the masses of refugees had been reaching the coasts for weeks. By masses I mean that every day, maybe 50 to 60 boats would land with an average of 50 people on board each of them. Thousands of people arriving every day. Although this had been the case since the summer, there was no large NGO or Greek or European institution with plans in place to receive these people, who are war refugees and have made a very hard and dangerous journey and arrive in conditions of maximum vulnerability.

So, what were people arriving at the coast met with?

There was an improvised solidarity circuit that could seem chaotic but was not. It was self-managed and there was a certain order. Out at see there were volunteer rescuers, along the coast there were points were people were received. People would of course arrive in a state of panic and it was very easy for them to lose what they were carrying or it could fall into the sea. Once on land, a team of volunteers would give them dry clothes, a hot meal, a space to change and we would try to calm them down and explain the next steps. On the coast there was also medical care and a place to spend the night if they arrived at night.

What were the steps after arriving on Greek soil?

At the time, the Greek Government allowed anyone arriving, regardless of nationality, to move freely around Greece for thirty days. Once in Lesvos, to get a permit, they had to go to a registration camp. There was one at Moria, for all nationalities (Iraqi, Iranian, Eritrean, Pakistani or Sub-Saharan) and Syrian men travelling alone, and one in Karatepe for Syrians. There they had to stand in a queue until they registered and got a permit. They could wait for up to 3 or 4 days. As far as I know, you could have up to 5,000 people and at Moria it could be a disaster; there were not enough tents to sleep in or food. Once they had registered and had their permits, they would then head for Athens, from where they would board a train or walked as far as needed to reach the North. These are the images we will remember from train stations in Germany.

Where did you get your materials and resources?

Mainly from individuals and groups that had emerged on the spot, who got donations from everywhere. Also, in Lesvos, there was a Greek anarchist movement that did a great job, and was able to provide food and clothes for many people. Sometimes, small individual actions would grow until they became a small NGO.

What tasks would you perform?

We joined the shifts that were already in place. We received people, meaning we helped them off the boats, calmed them down or helped them reunite with their families at a time of chaos. At the camps on the coast we also distributed clothes, offered them a place to sleep under a tent, set up camps (building shelters, installing taps...), we cooked, light fires so they could stay warm, provided information... Also, we did another task on our own accord, which was cleaning the beaches, because they were full of lifejackets, punctured rubber boats and personal items. The coastline of Lesvos was a large carpet of plastic and objects. I would like to stress the work done by a group of women, who started to wash clothes in an industrial laundrette. This was very important because it meant they didn’t throw away the clothes they arrived in (which used to happen) and that fewer donations were needed, as well as allowing people to wear clothes they had arrived with, making them feel more at ease. And finally, a task that may seem simple, that is talking to the refugees. A moment of normality to regain dignity after such a hard voyage.

"Women, who are already in a vulnerable position for being refugees, are even more so just because they are women”

How has reality changed in Lesvos since then?

We saw them building a camp on the Lesvos coast that in theory was to offer shelter to the people arriving. A huge project costing thousands of Euros. In March, however, the EU reached an agreement with Turkey, which put an end to the mass arrivals. This meant that the camp, which was the large UNHCR project on the coast, came late and was badly planned, because as a result of the deal with Turkey, it was never actually used. It’s empty. Today, because of the agreement, people are not arriving in masses. Now, refugees who arrive are arrested and awaiting deportation to Turkey at the Moria camp, which has gone from being a registration camp to a detention centre.

Have any of the answers provided by the EU worked?

The European Commission’s first proposal was a relocation scheme based on quotas for each State. The theory was that, from the registration camps, refugees would be informed of which countries offered reception. If the country offering to host refugees and the country of choice matched, then the Greek Government would cover the travel expenses. In practice this never happened. From when the quota scheme was adopted and until the agreement with Turkey, the Spanish State had not offered a single relocation space. Furthermore, the quotas were ridiculous. It could all have been much improved. At a logistical, human, political and moral level.

"It is important to have political advocacy for the refugees to get here"

What was the situation for women?

They are even more vulnerable. Many have been the victims of sexual aggressions along the way. There are pregnant women, ones who travel alone with many sons and daughters. In Lebanon, they face the problem of refugee women being sold, or teenage girls being sold to wealthy husbands or pimps. Overall, women, who are already in a vulnerable position for being refugees, are even more so just because they are women.

You have given conferences and been interviewed. Why?

Providing assistance on the spot won’t change anything. Your contribution is just a little grain of sand. What essentially needs to change is the conflict at origin and the policies of the countries that should take in migrants. Here we are faced with the dichotomy that Catalonia and many municipalities in Spain would want to receive migrants, but the State will not allow it. That is why is important to have political advocacy for the refugees to get here; but also to combat racism and fascism in a European context where they are on the rise. Anything we do to mobilise, do advocacy and raise awareness will be positive.

Where will we be 6 months from now?

Reality changes rapidly. Today the camps along the Macedonian border have been dismantled and most people are in military camps. They lack food, some are in very bad conditions and are lacking activities. The camp is like a psychological, mental and desert with no place for moods. And 6 months from now I think things will be worse. Policies are growingly restrictive and the routes are becoming more and more dangerous. I am not optimistic, but the only possible change will come from popular pressure.

Petra, June 2016

What camp where you at and what did you see there?

Since the end of June there are official camps, created by the Greek State, controlled by the army and managed, in some cases like Petra, together with humanitarian organisations. We spent one week at the Petra Camps, in northern Greece, and on the Macedonian border. At this camp you have Yazidi refugees, a Christian Kurdish minority in a country that no longer exists, Iraqi Kurdistan, disconnected from the rest of Kurdistan. It is a community that lives threatened in other camps and contexts and who gain some security in Petra. Most of the people arrive from Idomeni and say the conditions in the official camp are better. They have tents set up by professionals, drains, running water, WiFi, showers and chemical toilettes that are emptied every two to three days, blankets and food for subsistence; not much and always the same, but food after all.

What are the main problems?

Right now the basic needs are minimally covered, at least where we were. But what will these people do? And the children? Teenagers? They are not getting any training and don’t have any opportunities. What kind of a future will they have?

"If you really want to help, you must think of how to help, and not just arrive there thinking someone will give you a job to do; you must be informed and arrive there with the tools to make yourself useful"

How did you get there?

It isn’t easy for volunteers to access the official camps. It is channelled via an application to the Greek Government or through one of the organisations that have already done this. We got into Petra thanks to Álvaro Ruiz, from the Galdakano volunteers’ association; he was able to process our entry into an official camp.

What tasks do volunteers carry out?

With DSR we have provided primary dentistry care to more than 350 people. Pulling teeth, fillings, etc. Nothing requiring any further follow-up or treatment, because there’s nobody to do this. We have mobile medical equipment, so we took our own instruments and tried to be as independent as possible. I have seen many people arrive with empty hands and say: “I can build, what shall I do?” This is no way of improving, because there is no wood or tools there. I’ve even seen people arriving just to take a photo of themselves... If you really want to help, you must think of how to help, and not just arrive there thinking someone will give you a job to do; you must be informed and arrive there with the tools to make yourself useful.

Add new comment