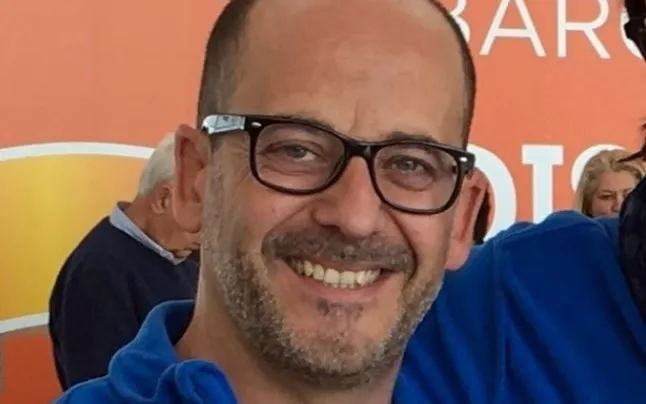

We spoke to the director of the NGO Ocularis, which is focusing its efforts on improving the visual health of the countries of the global South through training.

In Senegal there are four ophthalmologists per million inhabitants, in Mozambique the proportion drops to 0.7, while in Spain there are more than a hundred. If we talk about optometrists, Senegal has seven for every million inhabitants and Mozambique 1.1 for the 352 in Spain. This brutal imbalance is the main reason that pushed Dr. Joan Prat, Head of the Ophthalmology Service of the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu and an eminence in the specialty of oculoplasty, and Armand Valera to found in 2010 the NGO Ocularis.

The organization was born with a clear vision: to eradicate preventable blindness and fight for the universal and equal right to visual health, thus contributing to the elimination of poverty and the improvement of the quality of the population, especially children. Dr. Joan Prat had already worked for an NGO in Mozambique since 2005, and decided to start his work in that country. Today we are talking about Armand Valera, co-founder and current director of the NGO, which has expanded its activities beyond the borders of Mozambique and has a vocation to continue growing.

What is the philosophy that defines Ocularis?

We start from the premise that the raison d'être of international cooperation is to promote development, this has always been our mentality. Luckily, we've been leaving welfare behind for years. We think that without training, people in the countries of the global South will never be able to move forward.

It all started more than ten years ago in Mozambique.

At first, what we did was go to the country to offer training on Oculoplasty and eye tumors, the specialty of Dr. Prats; and pediatric optometry, because the team in this specialty at Hospital Sant Joan de Déu joined the project. At that time, we were teaching these two specialties and we were tailor-made for the main hospitals in Mozambique.

A country where there are very few doctors dedicated to visual health.

The comparisons with respect to Spain are brutal and even aberrant, I would say. While we have one ophthalmologist for every 12,000 people here, they have only one for every million people. This means, in short, that in Mozambique there is no public health in ophthalmology. People still go to the sorcerer or have no choice but to lose their eye when they have a serious problem. It's hard, but it is.

How has this training task evolved?

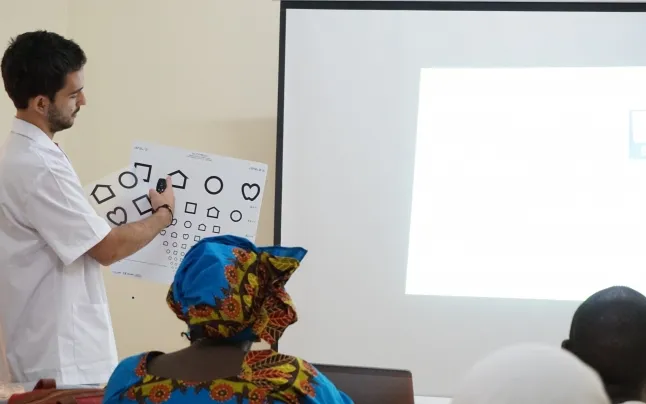

At first we trained only in hospitals, but we soon decided that we needed to progress and deepen in the purest development cooperation. We are very clear that training people is the key to development. That’s why we got closer to academia and now we work with public, medical and optometry colleges.

And what are you doing there?

We create postgraduate and master's courses and train faculty members so that they acquire this knowledge and, with our support and help, become the ones who can carry out this training work. That is, we train the trainers.

You did that, for example, with a postgraduate degree in pediatric optometry in Mozambique.

Exactly, we created the course at the Faculty of Health Sciences in Nampula, in the north of the country, and trained six teachers. And this year, registration will be open to any optometrist in the area. We will continue to support and go there two or three times a year to do practical classes at the university itself, alongside the teachers we have trained, so that they will absorb the knowledge and be themselves who, in the future, do this task.

And it's not the only project you're up to.

We are also developing a master's degree in oculoplasty and orbital tumors at the medical school of the capital's university, Maputo. In addition, we have two editions - and we have the third one ready - of a postgraduate diploma in pediatric ophthalmology at the Faculty of Health of the University of Dakar, Senegal, where we have been teaching for six years.

This course sells doctors from all over French-speaking Africa, such as Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, among others. The goal is always the same: to empower teachers so that they are self-sufficient and can teach the course without our help.

Visual health problems affect many people in the South, but they are relatively easy to avoid.

In fact, between 60 and 70% of children's vision problems are related to strabismus and myopia. And of course, without a professional putting glasses or a patch on their eye, the problem can become chronic, for life. And sometimes it would be as easy as that to put a patch or glasses with corrective graduation on it. The thing is, there are no professionals who can do that. This is not only the case with visual health, but with most diseases.

And that often has the worst consequences.

Is it like that. If a child is found to have a tumor in their eye, which is really small because the incidence is low, that child will surely die. This has not happened in the north for more than a century because the tumor is usually detected when it is small and the size of a blotch. And they take it away and it's over. There, however, any infection or problem in the eye can lead to death.

Your work has benefits far beyond visual health, why?

Let me give you an example: if a father, who has ten or twelve children, is fishing and cataracts, he will no longer be able to weave a net or go out to sea, and therefore will not be able to continue his work. All he has to do is take one of his children to be his guide and go begging. This means that this child, who is usually a girl, will have to leave school and his future will be ruined. And besides, because this father has lost his job, he will probably take two or three more children out of school to put them to work and bring money home.

In other words, all it does is perpetuate poverty. In this sense, we align ourselves with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and with our work we contribute to reducing poverty. If we heal a productive person, we break a chain of poverty and help keep it from becoming chronic.

Do you also do online training?

80% of our training is practical and done on site, but we have also set up an e-learning platform, managed by Ocularis, to train teachers at a distance, offer masterclasses, resolve any questions… aside, we always have open communication channels with the people there, either by WhatsApp or by any other means. We keep track. It is a tool that has worked very well in this time of pandemic. However, we are very clear that the training should be done in situ.

Because?

For several reasons. The first is that it has nothing to do with a tumor that you can find in Barcelona with one from Mozambique. If left untreated, tumors can become very large and disfigure the patient's face. This is no longer the case here, and this is not what the doctor we are training in your country will find.

The infrastructure is not the same either.

Exactly, there the resources, materials and tools are very precarious, and it makes no sense for them to be formed with modern tools that they will not have. And another thing: If you have a doctor there training for six months here, the hospital where he works will be without a doctor because there is only one. All this must be kept in mind.

Another branch of Ocularis is social action.

We have always tried to lend a hand. For example, we have traveled to refugee camps in Greece and witnessed people fleeing Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq, among others. Taking advantage of our travels, we have also been to orphanages and schools putting on glasses or whatever it takes. However, we have done it on time because we think it is a task that requires a lot of investment and has little real return.

And in Catalonia?

We collaborate with organizations such as the Catalan Refugee Aid Commission (CEAR-CCAR), which we call every three or four months and ask for help to make revisions or distribute glasses, among other actions, to newcomers. And we also raise awareness, for example during visual health week, in which we give talks, events and fairs in various cities. And most importantly, the talks we do at the optometry faculties, which allow us to raise awareness among people in our industry.

In general, do we pay enough attention to our visual health?

I think not. We should go to the optometrist at least once a year for a check-up, as we do with a dentist, for example. We believe that it is normal to lose your sight and many problems could be prevented by visiting the optometrist more often. The truth is that we do not pay enough attention to visual health; and it is very necessary, especially considering that we are much of the day looking at screens. This is a serious problem, especially for children.

Let's talk about the future: what are your plans for the future?

We are currently focusing on the third edition of the Ophthalmology Pediatrics Diploma at Cheick Anta Diôp University School of Medicine in Dakar. And we will evaluate if we export the project and take it to countries in the English-speaking part of Africa such as Kenya, Ethiopia or Ghana. We think it will be relatively easy to do, because we already have all the material and experience. And as for the vision for the future, we want to continue training the trainers, which is the basis of our action.

Add new comment