The Centre Delàs is an active part of the international campaign #StopKillerRobots, which calls for the prohibition of autonomous weapon systems that can make all decisions.

Autonomous weapon systems have been a growing concern in the realm of security and human rights. These weapons, capable of making decisions and carrying out lethal actions without human intervention, raise profound ethical and legal questions. What would a world be like in which machines could decide who lives and who dies?

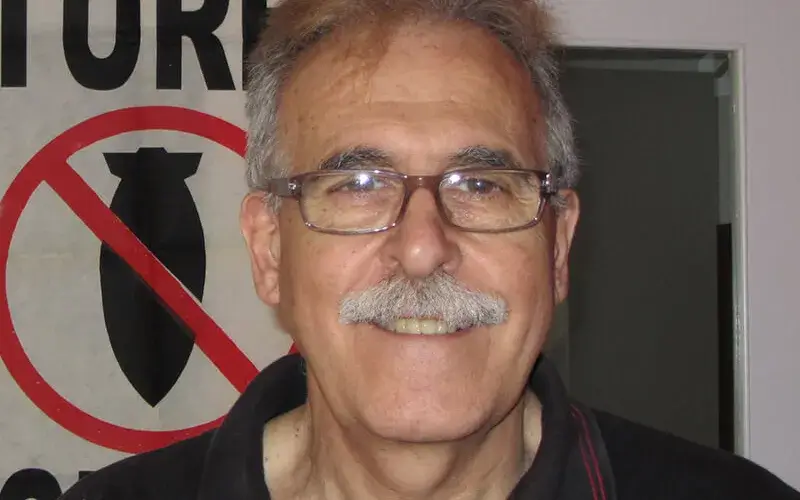

The #StopKillerRobots campaign aims to mobilize society and pressure governments to take action before it's too late. It's an international movement in which the Centre Delàs d'Estudis per la Pau is heavily involved. One of its founders, Tica Font, is also one of the most authoritative voices on the issue of autonomous weapons.

An expert in defense economics, arms trade, defense budgets, and the military industry, Font is very clear about the urgent need to halt the development and deployment of these weapons. Therefore, the first step is to raise awareness in society and turn the debate into a global fight: 'we need to put the issue on the table.'

How does an autonomous weapon system differ from an automatic one?

Autonomous systems are those where at no point has a human made the decision of whether to kill; instead, a computer has identified a target, tracked it, assessed the situation, and decided to fire or not. No human has been involved in these stages.

On the other hand, automatic weapons have a much more programmed decision system, with less margin for error; they are programmed like a washing machine. In autonomous systems, the margins of action are wide and very discretionary: it's the decision-making that a computer will do autonomously.

It's as if the computer has almost complete control.

Exactly, total control. The only human control here has been to design the program, the system, and input possible targets. Then, the computers will decide what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and so on.

Centre Delàs is part of the international #StopKillerRobots campaign, which calls for the prohibition of these weapons. What is your role?

We are participating in international debates, and in Spain, our goal is to raise awareness, to make it a topic on which the population must take a stance. We also try to campaign in universities—especially targeting law and computer engineering faculties.

And there's another focus of action, which is to exert pressure on the government. Sometimes, we hold sessions with some parliamentarians in the defense commission, and we also try to maintain a relationship with the Spanish ambassador handling this issue to make them see that there is opposition within society here."

What are the ethical implications of using these systems?

Firstly, are artificial intelligence algorithms as secure as those of a washing machine? Their algorithms are very precise: there's no improvisation, the washing machine doesn't decide if the laundry you've put in should or should not be spun. The machine is programmed to execute very established steps, and they are exact algorithms.

On the contrary, those of artificial intelligence are not exact algorithms. We've all used Google translations, but we also all know that once the text is translated, you have to review it; it helped you make the translation faster, but there are always errors. Therefore, we're using an artificial intelligence that inherently can always have errors, and the end result, in the case of weapons, could mean someone's death.

Legally, how could all of this be assessed? And what if an error occurs?

These decision-making algorithms cannot respect the pillars of international law. If there's an error, who will bear legal and criminal responsibility? What punishment do you give to a machine? Send it to a recycling point? Behind the decision of whether someone should die, there must be a human, and we must have a fully established chain of responsibilities.

They also do not comply with the principle of distinction: computers must be able to distinguish between a shepherd with an AK-47 and a Taliban member planning an attack; but they also have to decipher emotions, and that's impossible as of now. And it's the same when we talk about proportionality because the computer has to balance how many collateral victims it can execute; these are judgments of value and psychological nature, which a computer cannot make.

Is this type of weaponry already being used?

Do we know if it's being developed? Yes. Do we know if there are prototypes? Also. I would almost assure you that autonomously armed drones have been used in Ukraine, but I don't have fieldwork on that yet.

What's the state of the debate on an international scale?

There has been a debate on this topic at the United Nations General Assembly, and even industrialized countries agree that there needs to be reflection. No one says there can't be armed drones, but there should always be a human pressing the button, making the decision of whether to shoot or not: it shouldn't be the computer deciding, but a human.

The path will be very long because in these ten years, all that has been achieved is them saying, 'yes, we need to reflect on this topic.' And regarding the prohibition—which is what civil society is asking for—the reality is that none of the industrialized countries developing projects in these technologies are in favor of limitations.

And which are those countries?

All Western ones, the United States, and, among non-Western countries, for example, we have Israel, Iran, Turkey, Russia, China... All of them consider that limitations shouldn't be placed on the development of these technologies. Until something happens, and a significant part of humanity makes a global outcry saying 'this cannot be'... well, we'll see how difficult it is until then.

Do you think society is aware of the magnitude of this problem?

No, it's not aware, and I believe that in society—and especially among the younger generation—there's a fascination with technology, which makes this reflection difficult. We're not saying that we need to limit the number of hours spent on mobile devices or that social networks need restrictions or rules. What we're saying is that technology cannot decide who lives and who dies: that decision should be made by a human.

Is it essential to mobilize society for governments to take action?

In general, all governments are moved by public opinion polls, and if this issue doesn't mobilize people, why would the government oppose it if its population is not against it? This is an important element. The issue needs to be put on the table now that people are starting to become aware of what the use of artificial intelligence entails in many matters. But the debate about using this technology for killing is not yet part of society's concerns; until people are scandalized by something, that thing doesn't exist.

Is there also a lack of awareness about this issue in the European context?

The surprising thing is that it's the first time we have a budget in the European Union with a chapter dedicated to defense, and this chapter has two sources of funding: one line to subsidize states' purchases of weaponry and another for financing to help companies develop technologies for military use. The European Union lists the types of military research it wants to conduct and subsidizes them. That's the reality.

Who benefits from not prohibiting this type of weaponry?

In general, we could say that it's the industrialized countries that benefit, and will continue to benefit. And whoever develops new prototypes with artificial intelligence technology will have dominance over the economy. Therefore, it's a way to seek global economic preeminence, to make other countries dependent on you.

So, if it's an economic matter, how can institutions stop it?

There are also many countries that do not develop this technology and will not, they're just buyers. Our work is to try to have enough of these countries, within the United Nations assemblies, to exert pressure.

That's what we saw when the treaty banning the use of nuclear weapons was approved in 2017. The states that have nuclear weapons and the Western ones did not join and continue with their stance, but there are other countries that did, that are in favor of this treaty. It's important to see that not everything is controlled by Western countries at the United Nations. That's the hope: there are countries—not the poorest, but the intermediate ones—that can be relevant."

Add new comment