Almudena Barbero: “We all need to feel that we are important for someone and that if we go, we will be missed”

Almudena Barbero, the president of Nzuri Daima Foundation has been working for three years in one of the most conflictive areas in South Sudan, a territory marked by hunger and child suicide.

Almudena Barbero has lived in several African countries for the past 25 years leading the Nzuri Daima Foundation, which works to promote social change in areas struck by inequalities and human rights’ violations. This foundation has its headquarters in Barcelona and focuses on childhood using culture as a tool for transformation.

Following a community-based approach, it has been carrying out projects in South Sudan for three years. The country is marked by a war that started in 2013 and has led to the displacement of more than six million persons, 65% of whom are minors. According to the UNHCR, in 2023 there were 66,000 South Sudanese child refugees that are unaccompanied or separated from their parents. The child mortality rate is one of the highest in the world and, according to the UN, 4.5 million children in the country are in need of urgent humanitarian aid.

This was the context in which Almudena arrived in South Sudan, more concretely, in Yei, a territory where child poverty, hunger and violence are the norm. From Yei, Almudena shares with us what it’s like to fight for the life of young children every day and how we can help from Catalonia and Europe.

What is the current situation in South Sudan?

Theoretically the situation now is a post-war, but since there are still active armed groups, there is violence and instability in the region. This week a peace agreement was signed between several rebel groups and the Government and next Autumn there will be the first elections. Another reality is that, on the one hand, the instability caused by violence and several armed groups is stopping people from growing crops and getting other livelihoods because, even when they are able to plough the land, most of the time they are killed or robbed, and therefore nobody risks doing this.

On an economic level, the situation is becoming growingly complex because inflation has skyrocketed. The price of goods is up to seven times more than a year ago and people continue to earn very little, if they are lucky to earn anything at all. A year ago, eating was almost a miracle, and right now the situation is terrible.

The situation domestically is desperate. We are in the southern part of South Sudan, in Yei, one of the most difficult and dangerous areas because it borders with Congo and Uganda. It is the crossing point for most goods and rebel groups fight to control the area.

When did Nzuri Daima start working in this area of South Sudan and why?

We started working in South Sudan because the governor of Yei wrote asking us to go there. In one of his last emails, he wrote: ‘Please come, our children are committing suicide’. I found this very alarming; I’ve been working for 25 years in Africa, and I’d never seen such high rated of child suicide.

The day I arrived I met with a boy who’d been hung himself but was luckily alive. Many children are saved on time, but the percentage is terrifying: more than 33% of children under 12 in Yei have attempted at committing suicide and many more than once. An almost absolute majority see this as the only way out. And now, with the devaluation of the currency and the increase in prices, the situation is even worse. We’re also seeing a growing number of children sent to prison for petty theft.

Why do so many children consider suicide?

They have no food. On average, children go without eating three days per week. When you’re older, you become used to this, but the younger go to bed crying most days. They see they can’t go to school either. At Yei we have 50 schooling units, several under canopies or under a tree. They are asked to pay a schooling fee, and most cannot afford it. At the end of the day their despair pushes them to consider suicide.

In many cases they say it’s not so much about them being hungry but seeing their younger siblings crying and their mothers desperately finding a way to feed them. They think ‘if I get out of the way, that’s one less mouth to feed’. Then there are other reasons like being mistreated, or the very large number of orphans because of the war.

What are you doing at Nzuri Daima to try and revert this situation?

At the organisation we came up with the idea of paying the teachers’ salaries ourselves because the schooling fees for children are essential to pay salaries and the running costs of the schools. But in reality, very few can pay these fees and the schooling system is unstable. So, we reached an agreement with the governor whereby we provide incentives towards teachers’ salaries so the Government can gradually increase their wages, and families pay a fee that is used to ensure children eat at school, so they get at least one meal a day. And this means that families and communities make an effort to pay these fees. So far, we have implemented this system in six schools and it’s working well. In addition, once a week we contribute food to try and improve their diet. We believe a country with no education is a lost country.

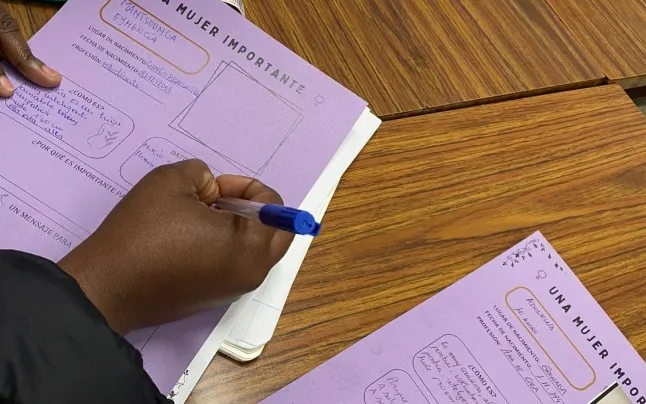

At the same time, we are using dance, circus, acrobatics, and music projects. We promote art and culture as a tool for transformation. We have set up circus and acrobatics group with more than 30 different ethnic groups in South Sudan. When children started, they thought they were totally uncapable of doing certain things, but then they realised this was a safe space where we offer them psychological support to heal their trauma. We started small and then expanded these projects to other schools.

Why go the extra mile instead of just ensuring food?

These activities take you out of the role of a victim and into that of a hero. Right now, boys and girls in Yei that participate in circus and acrobatics act in almost all national official events in the area and everyone goes to watch them. These children, who could have ended up on the streets, are now suddenly admired by others. For these children, it changes their position and also gives them a space to feel supported, and participating in something, being part of another family. At the end, we all need to feel that we are important for someone, and that if we go, we will be missed. This is what I believe is truly working with the circus groups and in schools.

We want to show them that they can have dreams, that they can stop being the poor child to become a child that is applauded and admired. Some of the children in these groups will travel to Spain to perform. We use music and art as a tool to explain things. Instead of explaining as a drama, doing so using a different language that may be easier to make them heard and shared. These are topics that call on us all.

What can we do in Europe to help improve these children’s lives?

To continue paying the salary incentives for the teachers at the schools in Yei we need to raise funds. Our aim is to reach at least €11,700 and ideally €585,000. That is why we have launched the campaign ‘Up against the ropes’ with the purpose of allowing people to make contributions to buy ropes or sponsor a school and cover the wages of teachers, so that we can ensure food for the children.

I understand that explained in this way it may seem far from our realities, but I’m sure we’ve all heard from our grandparents about the post-war years. It’s no different. Those generations that have been lucky to live free of wars can understand this and there’s no guarantee we won’t live a war in our lifetime. Our elders were given a helping hand and even if this was a long time ago, it’s equally fair and human to try and broaden our perspectives and help in those places where it’s needed, like South Sudan.

Add new comment