Eduardo Melero: "There are numerous traps and obstacles that hinder effective control of the arms trade"

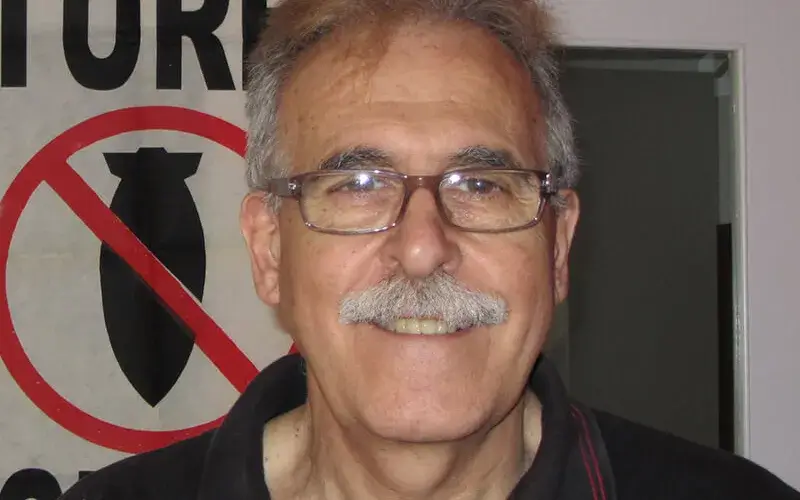

We delve into the world of arms trade with the authoritative voice of Eduardo Melero, an expert in the field and a researcher at the Centre Delàs.

There is no doubt that we are living in turbulent times, with an open war in the heart of Europe and an ongoing genocide in Palestine, among other ongoing conflicts. At the same time, we are witnessing a growing global militarization, reflected in the rise of military spending everywhere and fueling the lucrative war industry across the planet.

In this context, controlling and regulating the arms trade emerges as one of the critical challenges that must be urgently addressed if we want to create security on the planet. We discuss this in depth with Eduardo Melero, an expert in the field, Doctor and Professor of Administrative Law at the University of Madrid, and researcher at the Centre Delàs d'Estudis per la Pau.

How are arms exports regulated internationally?

There are several mechanisms to do so. One of them is the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), which came into force in December 2014. The agreement sets out general criteria that must be considered when authorizing arms exports. However, it has some issues.

What kind of issues?

For example, it does not establish any sanctions for violations. Nor does it formalize any international or intergovernmental body to oversee its enforcement. As a result, in the end, everything is left to the states, who are the ones responsible for ensuring compliance. In other words, we depend on the goodwill of the states.

Who else could act in this area, and I’m thinking specifically of the case of Israel?

The UN Security Council can impose arms embargoes in cases of threats to peace or acts of aggression, but this hasn’t happened, nor is it likely to happen. If it were proposed, the United States would probably use its veto power.

Could the European Union (EU), for example, impose an arms embargo?

It could do so even if the Security Council did not approve the embargo, as the EU's treaty allows it. However, there doesn't seem to be any intention, even in such a blatant case as Israel. One of the countries opposing it would be Germany, for example.

Could Spain do it?

Yes, Spain could also do it unilaterally through a decree law. In fact, various organizations from the campaign against the arms trade with Israel have presented a bill to include the embargo in Spain's arms trade law. Generally speaking, but especially to apply it to Israel.

How is this proposal progressing?

It is currently filed in the Congress of Deputies. First, the government must decide whether it considers the bill should be processed or not; after that, the chamber must vote by a simple majority to determine if it proceeds. We will see how it develops.

Are these arms embargoes common?

Not for Israel, but the UN Security Council and the EU regularly impose arms embargoes on certain countries. What the EU usually does is adopt an embargo if the Security Council approves it, although it’s true that on some occasions they have enacted this measure before the UN’s decision.

Why isn’t the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) applied to Israel?

If we look at Article 6.3 of the treaty, it clearly states that arms exports are prohibited if they are used to commit acts of genocide, crimes against humanity, and other war crimes. Therefore, in such an extreme case as Israel, it would be a perfect fit. However, as I mentioned before, everything is ultimately in the hands of the states. In this scenario, they have sided with the U.S. or Israel itself, and they are not adopting any real measures to prevent the arms trade with the Israeli state.

The Spanish government claims it has not authorized new military equipment sales licenses to Israel.

We’ve been told that no new arms export authorizations have been granted to Israel, but they have kept in place the licenses that were issued before October 7, 2023. Additionally, Delàs Centre researcher Alejandro Pozo discovered that in November, the company Nammo Palencia exported almost 900,000 euros worth of ammunition to Israel. This information was not disclosed. In fact, they said the opposite, but it has been proven that they are lying.

What other mechanisms does the EU have to regulate the arms trade?

There is the Common Position 2008/944/CFSP, which is intended as a regulation for arms exports by member states. However, the limitations are similar to those of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). There are no penalties for states that fail to comply with the criteria. It also doesn’t impose strict prohibitions but rather sets out certain conditions and factors that states must consider, allowing for some discretion in the application of the rules. Unfortunately, states, including Spain, are not being particularly strict in enforcing it.

Germany has already made it clear that it will continue exporting arms to Israel...

Yes, and it seems that EU law poses no obstacles because there are no EU institutions overseeing member states' compliance with this common position.

So, is there no European institution with jurisdiction in this area?

Indeed, the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU expressly excludes the competence of the European Commission (EC) and the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in matters of common foreign and security policy. This is noteworthy because the EC, for instance, monitors compliance with EU law in areas such as competition and environmental matters, among many others.

The arms trade, however, falls outside its oversight, and states cannot be brought before the ECJ for this either. So, once again, enforcement of this law is left to the good faith of the states. In short, we have legislation that theoretically prohibits or limits arms exports to countries that violate human rights or commit genocide, but in practice, there are no mechanisms to ensure compliance.

Broadening the scope, in the case of Spain, what type of arms does it mainly export?

Over the past decade, the primary defense material it has exported has been military aircraft, accounting for 75% of exports and worth around €30 billion. This doesn't mean only complete aircraft are exported; often, it's parts or components as well. Following this are warships, which represent 7% of exports, amounting to more than €2.6 billion. In third place are munitions, which make up 4% of exports and total about €1.6 billion.

To which destinations is this material exported?

More than 50% goes to EU and NATO countries, so from a human rights perspective, it shouldn’t be controversial. However, there is a clear trend of increasing exports to the Middle East, to countries such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, or the United Arab Emirates—regimes that violate human rights or are involved in conflicts. Exports to Asia are also on the rise. These trends are mirrored globally, with the U.S. being the top exporting country.

Does Spain have specific mechanisms to control arms exports?

We have Law 53/2007, under which the government acknowledges that the exported material is sensitive and subject to administrative authorization. This means that this material cannot be exported without prior administrative approval. A binding and mandatory report is issued, and then the Secretary of State for Trade grants formal authorization. However, the real decision on whether the export goes ahead is made by the Junta Interministerial Reguladora del Comercio Exterior de Material de Defensa y de Doble Uso. (JIMDDU).

Does this body exercise rigorous control?

It is responsible for ensuring that no material is exported to countries that may commit genocide or violate humanitarian law. However, in reality, the JIMDDU applies a very lenient and lax interpretation of the legal criteria. One of the more recent developments is the introduction of the possibility of conducting on-the-ground inspections, as the usual process is done on paper. However, this mechanism is still very new and hasn’t been widely used yet.

Is there a lack of transparency in this regard?

One factor that doesn’t help is that since 1967, the minutes of the JIMDDU have been classified as state secrets. If these documents aren’t public, it makes it difficult to know who is requesting authorizations and why they are granted.

Can these decisions be appealed in court?

Yes, in fact, this is another mechanism to ensure compliance by the Administration. There have been cases—for example, ten years ago, various organizations supporting the Sahrawi people requested the revocation of arms export authorizations to Morocco and took the case to the National Court.

What was the outcome of that request?

The official secrecy posed a significant problem and made it extremely difficult to present a well-argued appeal. This was also one of the reasons the court used to dismiss the petition. Now, the Palestinian Community of Catalonia has also requested the revocation of arms export authorizations to Israel. So far, however, the Administration has not responded, and the case is pending trial before the National Court.

So, accessing this information is always very challenging.

In general, there are numerous traps and obstacles that hinder effective control over the arms trade. Additionally, unfortunately, these topics are rarely present in public discourse, except on specific occasions. Perhaps due to the current conflict between Israel and Palestine, there is more media attention on arms trade issues, but in general, this is not a relevant topic nor is it on the public agenda. Without social pressure, it's hard to bring it to light.

And it seems the legislation isn’t very useful in this regard.

In reality, both European and Spanish legislation serve to legitimize these exports. The Spanish government always defends its strict compliance with the law on the matter, meaning that in the end, the legislation is used to justify an arms export policy that has many dark spots and is highly questionable. On the other hand, the law also grants legal certainty to exporters.

This is made very clear in the case of exports to Israel.

Indeed, the sad reality is that the controls in place are ineffective. And in such an extreme case as this, the fact that the legislation hasn’t led to any significant change says a lot about its practical effects. It’s more about legitimizing the arms trade than controlling it.

Do you expect this to change?

I'm not very optimistic. I've been working on arms trade issues for over twenty-five years, and the progress has been minimal. Some points in the legislation have been improved, and there have been advancements, but the results are meager. Today, Spain hardly denies 1% of requests to export arms. The reality is that human rights protection and conflict prevention are not on states' agendas—not even Spain's—or if they are, they play a very secondary role.

That’s not what they tell us publicly.

Because it’s much easier to adopt symbolic measures, like recognizing the Palestinian state. Meanwhile, military relations with Israel have remained essentially unchanged, and agreements are upheld, with arms being bought and sold as usual.

There’s a lot more talk about arms exports, but imports are also highly relevant.

Yes, and Israel’s case highlights this. It’s a country focused on imports and advertises its products as “battle-tested.” Therefore, even indirectly, buying arms from Israel supports the regime, its arms industry, and, consequently, the occupation of Palestinian territories. Regarding imports, according to current legislation, states have complete freedom. The ATT says nothing about it, and both Spanish and European laws only regulate exports.

How is that possible?

In terms of arms imports, we need better control mechanisms and, at the very least, to establish some minimum criteria. One of the things we propose is to explicitly ban the purchase of arms from countries that commit genocide or crimes against humanity. It’s the minimum if we don’t want to be complicit in such injustices.

As always, everything ends up depending on the states.

That’s one of the reasons I’m pessimistic. There’s very little political will on the part of states to strictly enforce what the law says and to use the tools recognized by the legal framework, like arms embargoes, to name one example. The mechanisms exist, but there is a lack of political will to apply them effectively.

Add new comment