The founder of Africa Stop Malaria and BonDiaMón denounces the devastating effects generated by Chinese fishmeal factories in the West African country.

No one in their right mind would believe that it makes sense to combat illegal fishing and overfishing by promoting the very practices that one seeks to fight against. This, broadly speaking, is what is happening with aquaculture and the fishmeal industry in countries like Gambia.

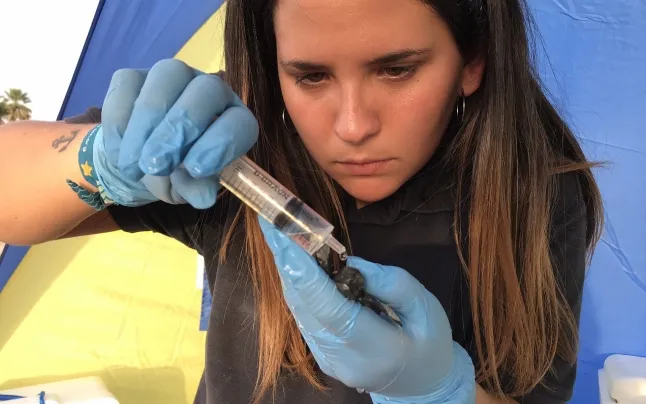

Noemí Fuster has witnessed this absurdity, which is causing severe impacts in multiple areas in the West African country, advancing hand in hand with Chinese companies that have installed their factories on the Gambian coast.

We speak with Noemí, an activist involved in denouncing injustices and defending environmental causes. All her work and the projects she undertakes can be followed closely through her Instagram account.

Who is Noemí Fuster?

I hold a PhD in microbiology from the University of Barcelona (UB), and in 2008 I founded my first NGO, Africa Stop Malaria. Through this organization, we organize volunteer trips to Gambia and Senegal during the rainy season to set up mosquito nets.

It's not the only NGO you have founded.

No, in 2016 BonDiaMón emerged, which initially was a YouTube channel to give visibility to small entities in the third sector. However, following my trips to Gambia and Senegal, I soon realized that with Africa Stop Malaria, we couldn't respond to all the demands we had, such as building a health center or other tasks. Thus, BonDiaMón became a non-profit organization, allowing us to undertake other projects, which have branched into areas such as food security and planetary health, among others.

What is your philosophy regarding cooperation?

It is very much related to the Mandinka word ‘Tesito,’ which means tightening the belt. This means that when we have a project at hand, we all need to tighten our belts, including the local community. At BonDiaMón, we carry out projects that arise from the local community and that we do together with them. If, for example, we build a health center, the local population provides the labor.

You distance yourself from assistentialism.

The idea is always to work as a team and not bring preconceived ideas from the Global North because they either won't work or are not a necessity. It is crucial that the community takes ownership of the projects because if not, they will not have a future.

Let's talk about the issue of fishing and the fishmeal industry in Gambia. What is the context?

Starting in 2016, the country undergoes a significant change: it frees itself from the dictator and opens up to foreign investment. And China enters through the front door, setting up three fish processing factories along the roughly thirty kilometers of coast that Gambia has. This industry transforms fish into fishmeal and fish oil, products that are widely used in aquaculture.

What is aquaculture?

Aquaculture is the controlled breeding of species that live in water. If we take a look at the Acuicultura de España website, it presents itself as the solution to overfishing and illegal fishing. Therefore, on paper, it seems great because we have been engaged in industrial fishing for many decades, and we are depleting the oceans. The idea, then, is to stop fishing and eat farmed fish. They themselves, for example, boast about achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), when the reality is that they do not meet a single one.

What is the problem?

The problem is that we are fishing to feed farmed fish. This is well summarized by a phrase from the former director of the Instituto de Acuicultura Torre de la Sal, José Miguel Cerdá Reverter, who says that we go to the sea to catch small fish that we do not like to eat in the global north, to turn them into feed to nourish species that we do like to eat. It is all very perverse and causes many problems, including losses. In the process of turning fish into meal, only one kilogram of fish meal can be obtained from every five kilograms of fish.

What impacts does this industry have in Gambia?

The fishmeal industry is causing very harmful impacts in Gambia, across multiple areas such as environmental, social, economic, and gender issues. For example, regarding the environmental aspect, which uncovered the whole situation in 2017, the lagoon of the Bolong Fenyo Wildlife Reserve, which is near one of these factories and has always been managed by the local community, was found one day dyed pink with all the animals dead.

And what happened?

A Gambian microbiologist analyzed the water and found heavy metals such as arsenic, phosphates, and nitrates. This triggered a sort of revolt, and the protests ended with damage to the factories. The next day, activists were jailed, the damages were repaired, and a Chinese flag appeared. Therefore, the dumping of toxic substances is one of the environmental problems caused by this industry.

It’s not the only problem.

No, there is also a lot of fish that ends up discarded and thrown away when the factories are over capacity, issues with the mesh size of the nets, which are not as they should be, or illegal fishing practices, among others.

You also mentioned social problems.

The situation, and I think this is unprecedented in Africa, has caused conflicts between young people and the elderly. On the continent, the elderly are highly valued and respected for their knowledge and experience, and of course, when the Chinese arrived, they approached this group and bribed them. In fact, if you walk through cities like Gunjur, the largest houses belong to those who have made deals with the Chinese. This has divided the population, with young people seeing their resources dwindling and clashing with those who collaborate with the Chinese.

The situation is very serious.

We can also talk about the precarious working conditions in the factories or the impact on ecotourism, which has suffered because the strong odors from the factories make it impossible to visit the area. Or the gender impacts, which have resulted in a significant decrease in women working as fishmongers who have now lost their jobs.

The Gambian population can no longer consume this fish…

Exactly, because the fish has become extremely expensive and is no longer accessible. The local community's diet relies heavily on bonga fish and sardinella, which are pelagic fish crucial to the food web, and these are two of the species most targeted by these factories. I have Gambian friends who tell me that they used to get these fish for free when they helped the fishermen, but now they are out of reach.

You managed to enter one of these factories. What did you see?

I got in thanks to a contact with the security personnel and a Chinese person who was there. I saw them loading containers with trucks. During the time I was there, they loaded two containers, each with a capacity for 420 sacks. I estimated that they unloaded over 200 tons of fish. This, in just one day and at the smallest of the three factories.

And the Gambian authorities allow it.

Everything is done with absolute impunity, opaquely, and with the approval of the Gambian Ministry of Fisheries. It is very serious; food insecurity is increasing in Gambia due to the impacts of this industry, and malnutrition in the country is exacerbating common diseases like malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea, among others.

So, should we consider aquaculture a problem?

Honestly, I think we need to reconsider it as consumers. We have the power to change things, and it can be done. As consumers, we are being deceived because we are supporting a perverse industry, and additionally, these fish farms are causing the fish to end up sick and full of parasites.

How should we act?

We need to finally accept that aquaculture is not sustainable and promote the consumption of local fish as much as possible. We have wonderful fish markets and fishermen's guilds that are struggling today because it is very difficult to find a generational replacement. Let's help them. And I also believe that we should promote other types of plant-based proteins to nourish ourselves beyond farmed fish. Let's take advantage of the wide range of possibilities available to us.

Add new comment