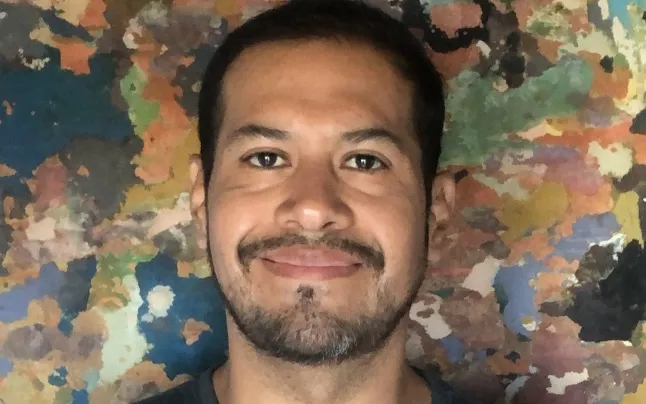

Karlos Castilla: “The goal behind National Adaptation Plans is to hold States accountable”

The lead researcher at IDHC calls for a preventive approach to the movement of persons that will be caused by climate emergency.

From the Institut de Drets Humans de Catalunya (IDHC) they are calling for the need to translate the human right to the environment, that is an internationally recognized right, into national legislation at a country level, to transform a vague and discursive concept into an effective binding norm.

Karlos Castilla, the lead researcher at the organization, says that since the alternatives to officially recognize environmental migration have reached a dead end, the only remaining option is to include it in policy at a country level independently as an imminent outcome of climate change and to work towards mitigating the associated risks.

Today there is an ongoing debate on the term “climate refugee”. What are your views on this matter?

From IDHC we are working on an alternative option to this discussion. The terms refuge and climatic have a complex background. This is why we are seeking to include an approach focusing on the environment, which is a broader term that climate, and we are doing this from National Adaptation Plans.

What are National Adaptation Plans?

They originate from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and are a mechanism to come up with an assessment of the risk situations in a country and design ideas to adapt and deal with these risks. They are all about improving transport, waste management and many other aspects.

Since 2010, the Cancun Adaptation Framework suggests including into these Plans aspects relating to displacement, migration and planned resettlement. This is what we are aiming to promote, for efforts to be made for the National Adaptation Plans that deal with environmental issues to also include the movement of persons.

We could say this is an alternative pathway.

Yes. The issue of refuge is linked to persecution and direct risks for a person, and it will be hard to overcome because of its historical implications. However, with the Cancun Adaptation Framework we could include a preventive approach instead of a reactive one to displacement and migration into the National Adaptation Plans. Talking about refuge means describing a risk situation that needs to be solved, and the idea is to avoid this situation from arising from the outset.

And does all this stem from the fact that international agreements and conventions fail to accept the status of climate refugee?

Yes. Work has been done in the past 15 to 20 years to ground the concept of climate or environmental refuge and migration. The latest opportunity to take a step forward in this direction came in 2018 with the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. However, this compact fails to include climate refugees and doesn’t foresee the option to include them.

Considering this situation, we believe it is impossible to find a way to give this category official recognition, we consider the pathway has reached a dead end. This is why we are trying to explore using the National Adaptation Plans, because they are mandatory for States.

Does this mean forcing action at a national level from the international arena?

Precisely. Using international law, the aim is to encourage countries to include measures for an orderly relocation of persons in a country or region where it is obvious that sea levels will rise, desertification will occur, or where there will be a loss of environmental resources…but always taking steps first to avoid this from happening.

The aim is to hold States accountable so that they take action before having to relocate the population, raise awareness on this possibility of this occurring and relocating in an orderly manner when there is no alternative, and including steps in their National Adaptation Plans. The bulk of the issue with environmental migration is and will be of a domestic nature, and not so much across borders.

Recently, the right to a healthy environment has been recognized internationally as a human right. What are the implications?

In July 2022, the Human Rights Council recognized the human right to a healthy environment, followed by the UN General Assembly. It recognises “the right to live in a clean, healthy and sustainable environment”, but this is not a treaty nor is it legally binding for states.

Nevertheless, the fact that more tan 155 States (representing 80% of UN members) have recognized the environment as a human right, and that this right is enshrined in legislation or a constitution, paves the way to resuming the discussion in these States and to promote a right that is not just collective, but also individual.

Add new comment