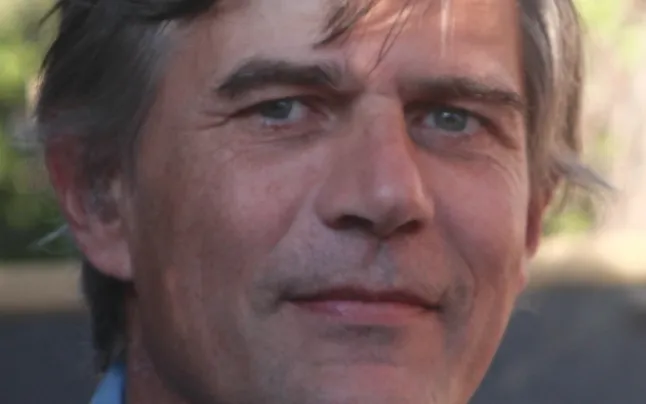

Philippe de Dinechin: "Organisations are born, grow and die, what matters are the seeds they leave behind"

The Comparte Foundation has been working for more than two decades to improve the lives of children in Latin America through educational projects.

For the Fundación Comparte, education is the key that opens all the doors to improve the lives of people, especially children. With this maxim, the organisation has been working for more than 20 years to guarantee the right to education of more than 15,000 children in Latin America. It does so through its support of seven local organisations in Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Honduras and Nicaragua.

A few days ago, the ‘Stars for peace’ festival organised every year by the foundation gathered about 5,000 people on the beach of Castelldefels in solidarity with the children of Nicaragua. We talked about all this with Philippe de Dinechin, one of the founders and the current director of the foundation.

How did a French citizen found an organisation in Barcelona focused on helping children in Latin America?

In 1998 I worked in France as a programme manager in Latin America and I thought it would be very interesting to create a foundation in Barcelona to help Latin American children, because here there is much more awareness regarding that part of the world than in France, my home country.

The city and its authorities welcomed our proposal and gave us a lot of advice. At that time, the 2004 Universal Forum of Cultures was being prepared, and everything went very well. We also had the help of Partage, a French association that works for the wellbeing of children.

The year you created the Fundación Comparte was also the year of Hurricane Mitch, which devastated Central America.

Yes, and coincidentally we were already working in Honduras, one of the most affected countries. In fact, one of the first actions we took was to raise awareness about the effects of the hurricane. We immediately received a great response from people and got a lot of support, which helped us get started.

Source: Fundació Paulo Freire.

Education is the bedrock of the foundation’s work, why did you decide it was the best way to help Latin American children?

There are many organisations in the world that work on urgent matters, which are very useful when there are major emergencies or crises. We, on the other hand, opted for a long-term vision, focusing on education to give a country’s children the tools to move forward.

And we’re not talking about any type of education, it’s not just about children learning to read and write. We’re talking about educating in values like solidarity, peace, and working on issues like conflict resolution. All of this is very important to us because the idea is to educate boys and girls in a country so that they become a generation of renewal, eager to contribute to their communities and societies.

You work in five Latin American countries. Do the educational needs in each country vary greatly?

Globally they are the same, but if we apply a more specific eye, they are quite varied. First, because we work in both urban and rural settings, and that in itself is already a very important difference. Another difference is the level of education: if we take Chile as an example, it’s a very solid country in this field, but education is very expensive and is very privatised from kindergarten to university. There, for example, we develop affordable nursery school projects for people with fewer resources.

Instead, in a very rural area like Santa Barbara, in Honduras, we have to build schools from scratch because there’s nothing. In short, we adapt to the reality of each country.

The Fundación Comparte always develops its projects through local organisations that you support.

It’s a fundamental aspect of the foundation. We believe that in Latin America there is highly trained staff at the educational level: educators, pedagogues and teachers of a very good standard. They know better than anyone what their people need and lack, but they don’t have the resources to act on that knowledge, which is why we support these organisations. We have been working with them for over 20 years and we know them very well, we are united by many ties. And they give us the security of a job well done. It’s not about imposing what we think is good, because they already know how to do it.

In these more than two decades of experience you have carried out all kinds of projects. Are there any that you’re especially proud of?

I have a special appreciation for the Educapaz project, which we have been doing for about 20 years. The idea is to work on conflict resolution with pre-schoolers. We made a handbook with 20 very specific activities in this regard. As an example, one of the activities is the ‘person of peace’, and it’s about asking the children which person represents peace for them. They usually choose people from the community who are benchmarks for them. One day, this person is invited to visit the classroom and they spend some time together. It’s a very beautiful activity.

What difficulties or challenges have you encountered along the way?

Perhaps the most complicated challenge is the instability that exists in many countries in the area. Honduras, for example, has always suffered from great political instability, with very corrupt governments. This is an impediment to collaborating with the state, to working together and carrying out our work.

Then there’s also the economic instability. In Argentina, for example, with the crisis of 2001, which dragged the entire middle class down and forced us to start practically from scratch. Thus, the great difficulty is maintaining long-term loyalty and programmes in very unstable contexts.

During the pandemic you did not stand idly by.

We thought it would be very interesting to do a study about the consequences that confinement provoked among children in each of the countries where we have a presence. We saw, for example, a significant increase in obesity and cyberbullying problems, among many others. Not to mention the lack of technological equipment, connection problems… Children were completely abandoned to their fate by states and schools.

The bottom line is that confinement wreaked havoc on children’s education in Latin America which will have lasting effects, and it led to a huge loss of confidence in states and schools. Thus, the children, who were the least at risk with Covid, were the ones who suffered the most.

Source: Foto cedida per Centre Cultural Hibueras.

And what about the sustainability of the projects?

In this sense, we decided from the beginning to use the sponsorship tool because it works very well with school and educational programmes. For example, if we have a school with 30 children, it’s a matter of finding 30 sponsors to support them. Taking into account the fact that two or three sponsors are lost every year for various reasons, you just have to look for two or three for the project to continue working. These are very long programmes, they run for 15 or 20 years, and this tool adapts very well to their goals.

You look for loyalty.

Yes, sponsorship has a lot to do with loyalty, a value which, by the way, is not fashionable at all nowadays. We are talking about the loyalty of the Comparte to local organisations, loyalty to children, of course, and the loyalty of the donor or sponsor, who contributes a monthly fee of twenty euros. So, although nowadays it may sound conservative, at Comparte we fight to rehabilitate the value of loyalty.

What future challenges does the Fundación Comparte set for itself?

I think organisations are born, grow and die. What matters are the seeds they leave behind. It’s like in life, a person before dying always wonders what they have sown in their lifetime. This is our philosophy. For us growth has never been a goal in itself, our desire is not to grow but to get things done the right way.

Add new comment