The report ‘Smart Borders, Negligent Democracies’, by Fundación porCausa and the Centre Delàs, warns that the digitalisation of border control in Europe is consolidating an opaque, privatised and weakly democratic system.

For years, Europe has embarked on an unstoppable race towards the criminalisation of people on the move. Human rights organisations have repeatedly warned about this, denouncing a growing militarisation, securitisation and control of borders that feeds the framework of Fortress Europe. For years, millions of euros have been invested in hindering inevitable movements, and worse still, with disastrous consequences from a humanitarian point of view.

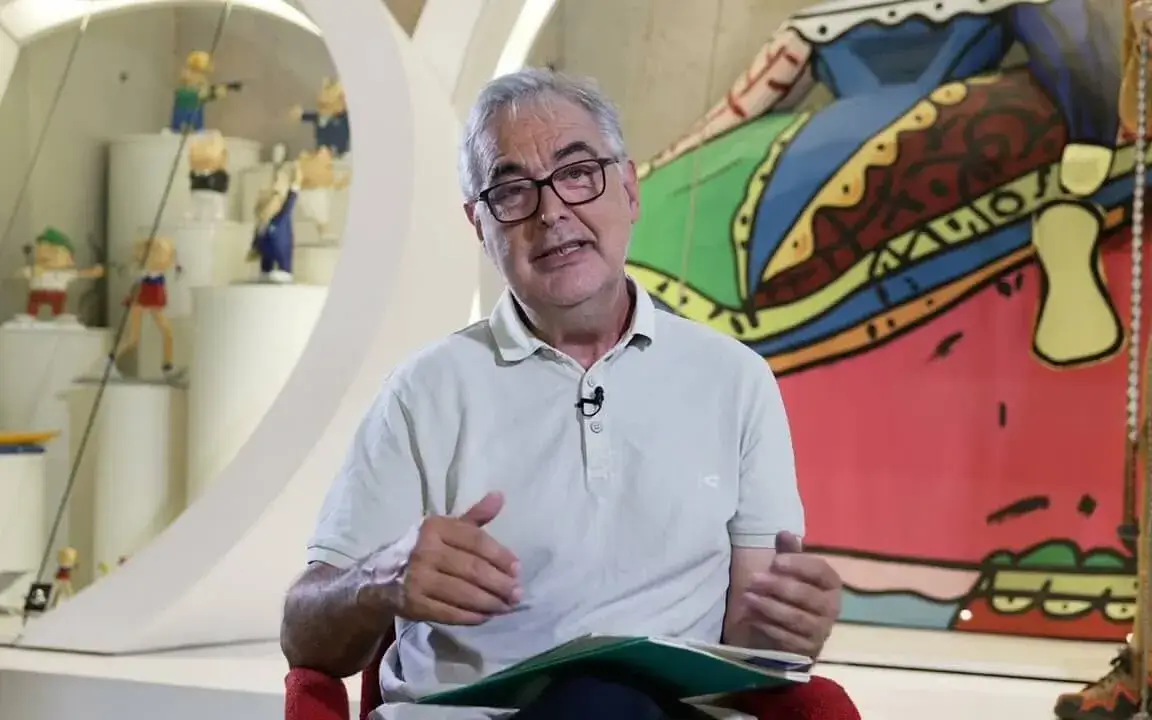

This drive for migration control has developed an entire industry —and a business— legitimised by European administrations, which has grown, been refined and become increasingly technified in parallel with the reinforcement of border fortification, institutionalising distrust and prejudice towards people on the move. In this context, Fundación porCausa and the Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau focus on a new phase of this model with the report ‘Smart Borders, Negligent Democracies’.

The document analyses how the massive incorporation of digital technologies —artificial intelligence, biometrics, predictive systems and automated surveillance, among others— is redefining migration control in Europe. Not to correct past abuses; quite the opposite, the report warns that this smart border consolidates a more opaque, more dehumanised system with serious impacts on fundamental rights.

From fences to algorithms

The study describes an evolution in three stages. First, the physical border: walls, fences, razor wire and obstacles designed to prevent passage. Then, the technologised and externalised border, with radars, sensors and remote surveillance that shift control beyond European territory, towards transit countries. And finally, the algorithmic border, an invisible infrastructure of data and programmes that no longer only monitors, but also classifies, predicts and decides.

In this third generation, the report warns, human decision-making is increasingly diluted. Profiling algorithms assign risk levels to people based on criteria such as their origin, route, documentation or behaviour. Biometric systems accumulate millions of facial and fingerprint records, while predictive programmes anticipate migratory flows in order to activate control mechanisms before people reach the border. All of this is presented under a promise of efficiency and neutrality that, according to the report, is profoundly misleading. “There is no possible neutrality when the starting point is distrust,” the document states.

In this sense, one of the realities the document highlights is that technology is not neutral. Automated systems reproduce the prejudices and inequalities embedded in the data on which they are trained and in the political decisions behind them. When these biases are transferred to an algorithm, they become the norm. “Human biases, previously dispersed and unpredictable, are institutionalised in code,” the report concludes.

As a result, this automation of migration control normalises discriminatory practices under a technical appearance. Decisions that previously required political or legal justification become the result of an opaque calculation that is difficult to challenge. “Technical opacity becomes democratic opacity,” it states. Thus, the risk is not only error, but the impossibility of knowing why it occurred and who is responsible.

An opaque system without democratic control

The lack of transparency is another pillar of the model. A large part of surveillance and control systems are awarded through unclear public contracts, often processed as negotiated procedures without publicity. Technical specifications use ambiguous language —“advanced solutions”, “intelligent analysis”, “detection systems”, the report cites— making it difficult to know exactly what is being purchased and with what safeguards.

This opacity has direct consequences, because these algorithms that end up influencing decisions on asylum, entry or expulsion are not subject to citizen or judicial oversight. “In practice, algorithms are treated as state secrets or, worse still, as private property,” the document mentions. Affected people cannot know the criteria that determined their case nor challenge them effectively. This erodes a basic principle of any rule of law, such as accountability, the report points out.

The document also focuses on the privatisation of migration control. Technology and defence companies have found a new market niche in border control. Systems originally conceived for military or police use are now adapted to the control of human mobility, with significant economic benefits for the companies that develop and commercialise them.

In the Spanish state, for example, a significant part of contracts related to border surveillance is concentrated in a small number of large companies. These corporations not only supply technology, but often also participate in the design and management of systems. The result is a transfer of sovereignty, in the sense that key decisions are left in the hands of private actors guided by commercial logics rather than respect for human rights.

Specifically, between January 2018 and October 2025, a very large part of the Spanish state’s contracts in the field of border surveillance was concentrated in just three companies: Escribano, Telefónica and Thales. If we broaden the focus to the European level, the same pattern is repeated with giants such as Airbus, Leonardo, Sopra Steria, Idemia or Atos, which are accumulating increasing weight in the migration control business.

Likewise, the report also identifies a worrying ideological homogeneity. European institutions, state governments and companies share a narrative that associates more technology with more security. And any criticism is dismissed as naïveté or resistance to progress.

This technological solutionism makes it possible to justify multimillion-euro investments in systems that have not been shown to improve the protection of lives, but have reinforced mechanisms of deterrence and expulsion. The smart border thus becomes a modern alibi to perpetuate a control model that prioritises order and suspicion over rights.

A warning about the future of democracy

Beyond migration policy, the report issues a troubling warning: what is applied today to migrants could be extended tomorrow to the rest of the population. “The technologies that today classify migrants are the same ones that tomorrow may classify citizens,” the authors warn.

For this reason, the report argues that the debate is not technological, but rather political. “It is not about rejecting technology, but about governing it,” the report states, pointing to the need to impose clear limits, such as transparency, effective human oversight, independent audits and real accountability mechanisms. Without this, they say, the smart border risks becoming a space of permanent exception.

‘Smart Borders, Negligent Democracies’ concludes with a sharp reflection: when security is built at the expense of rights, the price is not paid only by migrants, but by democracy as a whole. “The intelligence of the border ends up being the negligence of politics,” the document concludes.

Add new comment